讀俄人屠.....

據下英文,可知胡適讀的是Ralston的英譯本

胡適認知的屠格涅夫:宿命論者

楊建民《 中華讀書報 》( 2013年07月17日 18 版

胡適是一位博覽群籍的學者。當然﹐他是大學教授﹐要教學和研究﹐一般閱讀以學術典籍為主。可是﹐優秀文學作品幾乎對所有讀書人都有吸引力。對於堪稱“中國新文學”開山鼻祖﹑內在頗具浪漫情懷的胡適來說﹐他閱讀這些作品更有味﹐也很痴迷﹐閱讀之餘﹐常常還要作一番評議﹑研究﹐形諸文字﹐使我們今天還能見到他的閱讀感受﹐他富有學者意味的角度﹑視野。在國外留學期間﹐胡適所讀文學作品甚多﹐涉及國度﹑作家甚廣。這些作家中﹐胡適似乎對俄國的屠格涅夫有所偏好。從閱讀記述來看﹐這位大作家最為著名的《獵人筆記》及六部長篇﹐胡適統統讀過。不僅如此﹐在一個較為特別的時期﹐他還為這位大作家寫過一篇頗具水準的論文。中國新文學運動的先驅﹐對一位異國文壇名家進行研究﹐表現出異乎尋常的興趣﹐這可以引發我們今天的讀者留意。

胡適較早記述屠格涅夫﹐是他在美國留學時的1915年。當年1月20日﹐胡適到哈佛﹑劍橋訪友﹐與一幫中國學生“暢談極歡”。此時﹐友人鄭萊談到了屠格涅夫的一部作品。在當天的日記中﹐胡適這樣記述:“鄭君談及俄文豪屠格涅夫所著小說‘Vi“-gi〃S°i1’之佳。其中主人乃一遠識志士﹐不為意氣所移﹐不為利害所奪﹐不以小利而忘遠謀。滔滔者天下皆是也﹐此君獨超然塵表﹐不欲以一石當狂瀾﹐則擇安流而游焉。非趨易而避難也﹐明知只手挽狂瀾之無益也。志在淑世固是﹐而何以淑之之道亦不可不加之意。此君志在淑世﹐又能不尚奇好異﹐獨經營于貧民工人之間﹐為他人所不能為﹐所不屑為﹐甘心作一無名之英雄﹐死而不悔﹐獨行其是也。”(見《胡適日記全編》2卷)屠氏這部作品﹐當為《處女地》。胡適聽了友人講述﹐詳細複寫﹐並表示:“此書吾所未讀﹐當讀之。”到了當年8月31日﹐胡適果然尋到一部屠格涅夫的小說來讀。一讀之下﹐印象極佳:“讀俄人屠格涅夫名著小說《麗沙傳》。生平所讀小說﹐當以此最哀艷矣。其結章尤使人不堪卒讀。”(同上)這裡所謂《麗沙傳》﹐從情節和人物來看﹐應當是《貴族之家》吧。這之後很長時間﹐胡適文字中雖然較少出現閱讀屠格涅夫的記述﹐可從他偶爾談及作家的情況來看﹐對這位作家他並不陌生。有些意外的是﹐1930年1月16日的《中央大學半月刊》登出了胡適的一篇論述文字《宿命論者的屠格涅夫》。這段時間﹐胡適與友人一起﹐在《新月》雜誌上發表了一系列有關人權的文章﹐這引起了國民黨當局的不滿。當局利用報刊﹐對胡適進行圍攻﹐最後使得胡適不得不辭去中國公學校長職務。從時間來看﹐胡適寫作論述屠格涅夫的文章﹐正是與國民黨當局論爭的間隙。這倒是一個可以玩味的現象。《宿命論者的屠格涅夫》是一篇對這位大作家重要作品進行全面解讀的文章。胡適從結構﹑敘述﹑語言幾方面對屠格涅夫小說藝術給予評價﹐同時對這藝術的內涵作了哲學的導引:“屠格涅夫的小說﹐結構是那樣精嚴﹐敘述是那樣幽默﹐在他的像詩像畫像天籟的字句中﹐極平靜也極莊嚴的告訴了我們:人性是什麼﹐他的時代又是怎樣。讀他的每一篇小說﹐可以知道幾種典型的靜的人性﹐可以知道一個時期的動的時代。

讀他的幾篇有連續性的小說﹐可以知道人性的永恆不變時代的綿延變化﹐知道全人類的生活。”(見《胡適文集》第10冊《胡適集外學術文集》。以下引文同此。)是這樣的嗎?那麼﹐誰在主宰著人性呢﹐誰在推動著時代呢﹐誰又在播弄這時代和人性的關係及反應造成的人生呢?胡適說:“屠格涅夫告訴我們:這是自然。自然主宰著人性﹐自然推動著時代﹐自然播弄著這人生。”當然﹐這是胡適認為的屠格涅夫對世界的解讀:“屠格涅夫感覺到這個﹐認識到這個﹐也忠實的描寫了這個﹐所以在他的縱橫交織著時代和人性的作品下﹐顯示了不可理解的人生﹐在這個人生下﹐又潛伏著一個無情的運命之神。激動了讀者的情感的﹐是這運命之神。威脅著讀者的思想的﹐也是這運命之神。”按照這樣的解讀﹐胡適的結論出來了:“屠格涅夫是一個宿命論者。”為論述方便﹐胡適先將作品人物進行了類的劃分:“然將自己的自我置在第一位的﹐就是所謂哈孟雷特型﹐是為我主義者﹐是信念的狐疑者。將其他東西置在第一位的﹐就是所謂堂克蓄德型﹐是自我犧牲者﹐是真理───自己認為真理───的信仰者﹐屠格涅夫以為無論誰﹐如不類似哈孟雷特一定類似堂克蓄德﹐這兩種人性都是自然的﹐當然不能評判誰善誰惡誰真誰偽誰美誰丑。”(“哈孟雷特”今譯“哈姆萊特”;“堂克蓄德”今譯“堂吉訶德”───引者注。)從人類群體觀察﹐“哈姆萊特”性格的人居多數﹐可既然是人類靈魂的觀察﹑解剖者﹐屠格涅夫的認識顯然不會那麼單調。據胡適分析﹐他的筆下﹐也有“堂吉訶德”一類的人物。這些人物所具的

特點:“都是為了自己所信仰的一件事﹐負起責任﹐犧牲了自己。幻滅的悲哀﹐失戀的痛苦﹐也許不是常人所能受的﹐但他們有一顆堅強的心﹐都像堂克蓄德騎上他的洛齊難戴樣闖進了世界﹐追求他們的目的!”(“洛齊難戴”﹐是堂吉訶德所騎的瘦弱的老馬───引者注。)據此﹐胡適對這位俄國大家進行了概括:“屠格涅夫的人性論是二元論﹐認定這二元論是一個人生的全部生活的根本法則。他說:‘人的全部生活﹐是不外乎繼續不斷忽分忽合的兩個原則的永久的衝突和永久的調節’﹐屠格涅夫不批評這兩種人性的優劣﹐堂克蓄德也許能做一點事﹐哈孟雷特卻也有一種破壞力量。人性本是自然的﹐根據人性的發展﹐在事實上能成就些什麼﹐怕也祗有命運能決定罷!”最後一句話﹐似乎包含了胡適自己的認知意味。寫到這裡﹐胡適一下子把文章主題點了出來:“人性是命運決定的﹐時代也是命運決定的﹐人性和時代反應出來的人生﹐還是命運決定的!”該文的題目是《宿命論者的屠格涅夫》﹐可結尾卻不提屠格涅夫了﹐用的是宿命論者對世界的飄忽眼光和知解。從胡適的陳述筆調看去﹐也似乎並未對這種“宿命論”加上什麼批評的看法甚至字眼﹐是讚同嗎?胡適沒有明確表露;當然也不是非議﹐我們從整篇文章的無論分析或者評述都找不出非議的觀點或態度;從大量的文章和胡適的一生總體作為來看﹐他絕不能歸為“宿命論者”的行列。可是﹐他為何突然(胡適此前許久已經不大專門研讀外國小說﹐甚至中國新文學了)對屠格涅夫感起了興趣﹐並且給這位俄國大作家加附了“宿命論者”的徽銜

(從大量對屠格涅夫的研讀文字看﹐似乎很少如此看待他的人生觀)?不好說﹐我們祗好站在理解人性的角度﹐認為胡適此時由於某事﹐回首人生﹐產生了莫名的“宿命”情緒﹐藉著屠格涅夫的“酒杯”﹐表達自己人生某個時期的特別認知﹐“澆”內心難為人所知所解的“塊壘”。這﹐應當是可能的。從整個人生經歷來看﹐胡適對屠格涅夫的認知﹐並不顯得多麼重要﹐可是﹐作為中國新文學的先驅人物﹐他的聲音﹐在當時十分響亮。這一點﹐胡適是清楚的。這一次﹐他大大下了一番工夫﹐將屠格涅夫的重要作品閱讀一過﹐一一評點﹐由其中得出作者是“宿命論者”的結論。這結論無論確切與否﹐都是中國一位在哲學﹑文學等方面都有相當造詣的學者的一個判斷﹐因而是值得關注的。當然﹐從胡適的行文來看﹐他並非僅僅為得出這樣一個結論﹐他對屠格涅夫的研讀顯然有某種程度的傳達﹐表述“宿命”的別樣意味在其中。這雖然使我們產生一些困惑﹐可文字俱在﹐我們不得不承認﹐這是中西兩位傑出作家﹑學者碰觸之後產生的火花。這火花無論炫目或黯淡﹐都並非如煙一般飄忽消散﹐它將引發我們的矚目﹑思考。至於能從中收益多少﹐那就是個人性格﹑生存道路﹑時代際遇所決定的了。

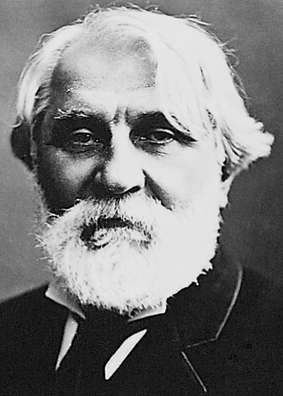

Ivan Turgenev AKA Ivan Sergeevich Turgenev AKA Ivan Sergeevich TurgenevBorn: 9-Nov-1818 Birthplace: Oryol, Ukraine, Russia Died: 3-Sep-1883 Location of death: Bougival, France Cause of death: unspecified Remains: Buried, Volkoff Cemetery, St. Petersburg, Russia Gender: Male Race or Ethnicity: White Sexual orientation: Straight Occupation: Author Nationality: Russia Executive summary: Fathers and Sons Russian novelist, the descendant of an old Russian family, was born at Orel, in the government of the same name, in 1818. His father, the colonel of a cavalry regiment, died when our author was sixteen years of age, leaving two sons, Nicholas and Ivan, who were brought up under the care of their mother, the heiress of the Litvinovs, a lady who owned large estates and many serfs. Ivan studied for a year at the university of Moscow, then at St. Petersburg, and was finally sent in 1843 to Berlin. His education at home had been conducted by German and French tutors, and was altogether foreign, his mother only speaking Russian to her servants, as became a great lady of the old school. For his first acquaintance with the literature of his country the future novelist was indebted to a serf of the family, who used to read to him verses from the Rossiad of Kheraskov, a once celebrated poet of the eighteenth century. Turgenev's early attempts in literature, consisting of poems and trifling sketches, may be passed over here; they were not without indications of genius, and were favorably spoken of by Bielinski, then the leading Russian critic, for whom Turgenev ever cherished a warm regard. Our author first made a name by his striking sketches "The Papers of a Sportsman" (Zapiski Okhotnika), in which the miserable condition of the peasants was described with startling realism. The work appeared in a collected form in 1852. It was read by all classes, including the emperor himself, and it undoubtedly hurried on the great work of emancipation. Turgenev had always sympathized with the muzhiks; he had often been witness of the cruelties of his mother, a narrow-minded and vindictive woman. In some interesting papers contributed to the "European Messenger" (Viestnik evropy) by a lady brought up in the household of Mme. Turgenev, sad details are given illustrative of her character. Thus the dumb porter of gigantic stature, drawn with such power in Mumu, one of our author's later sketches, was a real person. We are, moreover, told of his mother that she could never understand how it was that her son became an author, and thought that he had degraded himself. How could a Turgenev submit himself to be criticized? The next production of the novelist was "A Nest of Nobles" (Dvorianskoe gniezdo), a singularly pathetic story, which greatly increased his reputation. This appeared in 1859, and was followed the next year by "On the Eve" (Nakanunge) -- a tale which contains one of his most beautiful female characters, Helen. In 1862 was published "Fathers and Children" (Otzi i Dieti), in which the author admirably described the nihilistic doctrines then beginning to spread in Russia. According to some writers he invented the word "nihilism." In 1867 appeared "Smoke" (Dîm), and in 1877 his last work of any length, "Virgin Soil" (Nov). Besides his longer stories, many, shorter ones were produced, some of great beauty and full of subtle psychological analysis, such as Rudin, "The Diary of a Useless Man" (Dnevnik lishnago chelovieka), and others. These were afterwards collected into three volumes. The last works of the great novelist were "Poetry in Prose" and "Clara Milich", which appeared in the "European Messenger." Turgenev, during the latter part of his life, did not reside much in Russia; he lived either at Baden Baden or Paris, and chiefly with the family of the celebrated singer Viardot Garcia, to the members of which he was much attached. He occasionally visited England, and in 1879 the degree of D.C.L. was conferred upon him by the university of Oxford. He died at Bougival, near Paris, on the 4th of September 1883. Unquestionably Turgenev may be considered one of the great novelists, worthy to be ranked with Thackeray, Dickens and George Eliot; with the genius of the last of these he has many affinities. His studies of human nature are profound, and he has the wide sympathies which are essential to genius of the highest order. A melancholy, almost pessimist, feeling pervades his writings, a morbid self-analysis which seems natural to the Slavonic mind. The closing chapter of "A Nest of Nobles" is one of the saddest and at the same time truest pages in the whole range of existing novels. The writings of Turgenev have been made familiar to persons unacquainted with Russian by French translations. There are many versions in English, among which we may mention the translation of the "Nest of Nobles" under the name of "Lisa", by Ralston, and "Virgin Soil", by Ashtoil Dilke. There is also a complete and excellent translation by Mrs. Garnett. |

沒有留言:

張貼留言