David Hawkes Archive 消息( 張華提供)

Obituary

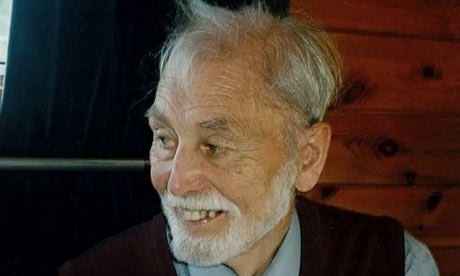

David Hawkes

Scholar who led the way in Chinese studies and translated The Story of the Stone

Hawkes's translation of The Story of the Stone for Penguin Classics retains the realism and poetry of the original

When the poet and critic William Empson spotted some neglected

correspondence on the desk of the president of Beijing University

(Beida) in Chiang Kai-shek's China, he transformed the life of David

Hawkes, the great translator of Chinese literature, who has died aged

86.

The letters were from Hawkes, then a young student of Chinese at Oxford University, who was so determined to continue his studies in China that he had taken passage for Hong Kong without waiting for a reply. Hu Shi, the famous scholar who headed Beida, was known to boast that he never bothered to deal with letters, so Empson – the only foreigner at the university – took immediate action and Hawkes was accepted as a graduate student.

It was 1948, the last year of Chiang's crumbling rule before the communist revolution succeeded. The Beida campus was still within the city (it moved later to its present location in the suburbs) and Hawkes found a hostel room in one of the ancient hutong lanes.

Beijing was soon under siege from the People's Liberation Army, and light and water became in short supply. Hawkes would help fetch cans of water on a trolley from a well that the students had dug. When the lights went out they all put their tables in the corridor and played games or told stories – excellent language practice for the British student. On 1 October 1949, when Mao Zedong proclaimed the inauguration of the People's Republic, Hawkes joined his fellow students to celebrate in Tiananmen Square, though Mao's declaration, in a thick Hunanese accent, was incomprehensible to them all.

As the different columns marched below the Gate, each contingent called out "Chairman Mao, long life!", to which Mao replied "Comrades (tongzhimen), long life!" The Beida students, Hawkes would recall, claimed that they had been singled out by the Chairman for a special mention – he had called out "Fellow students (tongxuemen), long life!" in recognition of Mao's past connection with the university – but they had probably just misheard.

Hawkes would remember the special character of old Beijing – long since vanished – all his life: "I can go around it in my dreams," he told an interviewer in 1998, "as if it were 50 years ago," and proceeded to describe by name its streets, gates, and dusty hutongs.

It remained only a dream, for he never returned after leaving in 1951: his wife-to-be, Jean, had joined him in Beijing, where they married after long negotiation with the local police station. Jean became pregnant, the Korean war started, and the couple were "very strongly advised" to go home.

Hawkes was born and grew up in east London and won a place at Christ Church, Oxford, where he read a shortened first part of the classics degree, before being recruited to learn "military Japanese" in London. Showing an aptitude for oriental languages, he soon became an instructor, teaching intelligence operatives and code-breakers how to interpret Japanese battle reports. Returning to Oxford in 1945, Hawkes switched from classics to Chinese and was, for a time, the only student in a department with only one teacher, the ex-missionary ER Hughes.

It was Hughes who persuaded the university to offer an honours degree in Chinese, but according to Hawkes he had "to make Chinese look as much as possible like Latin and Greek", with the syllabus limited to the study of Confucius and other classical texts.

Returning again to Oxford from China in 1951, Hawkes joined a small but growing department under the new professor – also ex-missionary – Homer Dubs. The syllabus edged forward with relatively more modern texts taught by Hawkes and by a new Chinese colleague, the talented Wu Shichang.

By the end of the 1950s, the set texts for undergraduates included popular fiction from the Ming dynasty and short stories by the famous 20th-century writer Lu Xun (though the study of Chinese history stopped firmly at 1911, at the end of the last imperial dynasty).

Through Hawkes's lively exposition we began to grasp the vitality and humanity of China and the Chinese, which were harder to discern in the classical canon. Guided by Wu we also plunged, dictionaries at close hand, into the first five chapters of the massive and psychologically complex 18th-century novel by Cao Xueqin usually known as the Dream of the Red Chamber (Hongloumeng) and regarded as the greatest work of traditional Chinese fiction.

Wu was already a recognised Hongxuejia – literally Red-ologist – while Hawkes had become fascinated by the Dream after discovering it in Beijing. In 1959, Hawkes published an authoritative study of the Songs of Chu (Chuci), an anthology of ancient poems from southern China, based on his doctoral thesis. In the same year he succeeded Dubs as Professor of Chinese.

Encouraged by Wu, who became a lifelong friend, Hawkes was always conscious of the greater challenge of the Dream. When approached by Penguin Classics in 1970, he leapt at the chance to produce a less academic translation, which would be more "enjoyable for the English reader". Before long, the magnitude of this work – the complete text has 120 chapters – convinced Hawkes that it had to be a full-time task.

With a very Chinese kind of self-deprecation, he argued that he "never saw himself as a very good professor", and that he would make a better translator. The world of China studies was shaken by the news that Hawkes had resigned his chair.

Over the next 10 years, helped by a research fellowship at All Souls, he completed the first 80 chapters in three volumes (1973, 1977 and 1980) under the Dream's original title, The Story of the Stone. The final 40 chapters, which only came to light after Cao Xueqin's death, would be translated by Hawkes's son-in-law, the sinologist John Minford.

Hawkes had hoped to return to China during a sabbatical in 1966, but this marked the beginning of Mao's cultural revolution, which he regarded with dismay. He would visit the Chinese embassy in London to protest at the imprisonment of his former fellow-students (and prolific fellow-translators of Chinese literature) Gladys Yang and Yang Xianyi.

After completing the Dream, Hawkes moved to Wales, where he revised his work on the Songs of Chu, also for Penguin Classics, and developed new interests in gardening, goats, Welsh and the history of religion.

Though he professed to have retired from China scholarship, in recent years he published a verse translation of the Yuan dynasty drama Liu Yi and the Dragon Princess, and took a close interest in the work of the Chinese poet Liu Hongbin, who fled China after the 1989 Beijing massacre.

Hawkes will be remembered for his translation of the Dream/Stone, not only as the most knowledgeable Red-ologist outside China, but for his inspiration and skill in conveying both the realism and the poetry of the original work. In doing so, he stepped far beyond the China field and his opinion of Arthur Waley, the pioneer translator of Chinese poetry, who was a close friend until he died in 1966, could well be applied to Hawkes himself: "[Waley] belonged not only to the world of oriental studies but to the world of literature."

He is survived by his wife, Jean, three daughters, Rachel, Verity and Caroline, and his son, Jonathan.

•David Hawkes, Chinese scholar and translator, born 6 July 1923; died 31 July 2009

The letters were from Hawkes, then a young student of Chinese at Oxford University, who was so determined to continue his studies in China that he had taken passage for Hong Kong without waiting for a reply. Hu Shi, the famous scholar who headed Beida, was known to boast that he never bothered to deal with letters, so Empson – the only foreigner at the university – took immediate action and Hawkes was accepted as a graduate student.

It was 1948, the last year of Chiang's crumbling rule before the communist revolution succeeded. The Beida campus was still within the city (it moved later to its present location in the suburbs) and Hawkes found a hostel room in one of the ancient hutong lanes.

Beijing was soon under siege from the People's Liberation Army, and light and water became in short supply. Hawkes would help fetch cans of water on a trolley from a well that the students had dug. When the lights went out they all put their tables in the corridor and played games or told stories – excellent language practice for the British student. On 1 October 1949, when Mao Zedong proclaimed the inauguration of the People's Republic, Hawkes joined his fellow students to celebrate in Tiananmen Square, though Mao's declaration, in a thick Hunanese accent, was incomprehensible to them all.

As the different columns marched below the Gate, each contingent called out "Chairman Mao, long life!", to which Mao replied "Comrades (tongzhimen), long life!" The Beida students, Hawkes would recall, claimed that they had been singled out by the Chairman for a special mention – he had called out "Fellow students (tongxuemen), long life!" in recognition of Mao's past connection with the university – but they had probably just misheard.

Hawkes would remember the special character of old Beijing – long since vanished – all his life: "I can go around it in my dreams," he told an interviewer in 1998, "as if it were 50 years ago," and proceeded to describe by name its streets, gates, and dusty hutongs.

It remained only a dream, for he never returned after leaving in 1951: his wife-to-be, Jean, had joined him in Beijing, where they married after long negotiation with the local police station. Jean became pregnant, the Korean war started, and the couple were "very strongly advised" to go home.

Hawkes was born and grew up in east London and won a place at Christ Church, Oxford, where he read a shortened first part of the classics degree, before being recruited to learn "military Japanese" in London. Showing an aptitude for oriental languages, he soon became an instructor, teaching intelligence operatives and code-breakers how to interpret Japanese battle reports. Returning to Oxford in 1945, Hawkes switched from classics to Chinese and was, for a time, the only student in a department with only one teacher, the ex-missionary ER Hughes.

It was Hughes who persuaded the university to offer an honours degree in Chinese, but according to Hawkes he had "to make Chinese look as much as possible like Latin and Greek", with the syllabus limited to the study of Confucius and other classical texts.

Returning again to Oxford from China in 1951, Hawkes joined a small but growing department under the new professor – also ex-missionary – Homer Dubs. The syllabus edged forward with relatively more modern texts taught by Hawkes and by a new Chinese colleague, the talented Wu Shichang.

By the end of the 1950s, the set texts for undergraduates included popular fiction from the Ming dynasty and short stories by the famous 20th-century writer Lu Xun (though the study of Chinese history stopped firmly at 1911, at the end of the last imperial dynasty).

Through Hawkes's lively exposition we began to grasp the vitality and humanity of China and the Chinese, which were harder to discern in the classical canon. Guided by Wu we also plunged, dictionaries at close hand, into the first five chapters of the massive and psychologically complex 18th-century novel by Cao Xueqin usually known as the Dream of the Red Chamber (Hongloumeng) and regarded as the greatest work of traditional Chinese fiction.

Wu was already a recognised Hongxuejia – literally Red-ologist – while Hawkes had become fascinated by the Dream after discovering it in Beijing. In 1959, Hawkes published an authoritative study of the Songs of Chu (Chuci), an anthology of ancient poems from southern China, based on his doctoral thesis. In the same year he succeeded Dubs as Professor of Chinese.

Encouraged by Wu, who became a lifelong friend, Hawkes was always conscious of the greater challenge of the Dream. When approached by Penguin Classics in 1970, he leapt at the chance to produce a less academic translation, which would be more "enjoyable for the English reader". Before long, the magnitude of this work – the complete text has 120 chapters – convinced Hawkes that it had to be a full-time task.

With a very Chinese kind of self-deprecation, he argued that he "never saw himself as a very good professor", and that he would make a better translator. The world of China studies was shaken by the news that Hawkes had resigned his chair.

Over the next 10 years, helped by a research fellowship at All Souls, he completed the first 80 chapters in three volumes (1973, 1977 and 1980) under the Dream's original title, The Story of the Stone. The final 40 chapters, which only came to light after Cao Xueqin's death, would be translated by Hawkes's son-in-law, the sinologist John Minford.

Hawkes had hoped to return to China during a sabbatical in 1966, but this marked the beginning of Mao's cultural revolution, which he regarded with dismay. He would visit the Chinese embassy in London to protest at the imprisonment of his former fellow-students (and prolific fellow-translators of Chinese literature) Gladys Yang and Yang Xianyi.

After completing the Dream, Hawkes moved to Wales, where he revised his work on the Songs of Chu, also for Penguin Classics, and developed new interests in gardening, goats, Welsh and the history of religion.

Though he professed to have retired from China scholarship, in recent years he published a verse translation of the Yuan dynasty drama Liu Yi and the Dragon Princess, and took a close interest in the work of the Chinese poet Liu Hongbin, who fled China after the 1989 Beijing massacre.

Hawkes will be remembered for his translation of the Dream/Stone, not only as the most knowledgeable Red-ologist outside China, but for his inspiration and skill in conveying both the realism and the poetry of the original work. In doing so, he stepped far beyond the China field and his opinion of Arthur Waley, the pioneer translator of Chinese poetry, who was a close friend until he died in 1966, could well be applied to Hawkes himself: "[Waley] belonged not only to the world of oriental studies but to the world of literature."

He is survived by his wife, Jean, three daughters, Rachel, Verity and Caroline, and his son, Jonathan.

•David Hawkes, Chinese scholar and translator, born 6 July 1923; died 31 July 2009

沒有留言:

張貼留言